Imagine how your son or daughter would feel if you were in prison.

Abandoned.

Ashamed.

Alone.

Sadly, this is the reality for 2.7 million children and youth in America today.

The brokenness and pain of having an incarcerated parent often begins a dangerous cycle of poor decision-making — ultimately leading to incarceration of the child later in life.

Today’s imprisonment rate is five times as high as in 1972 and surpasses that of all other nations. The sheer scale and acceleration of U.S. prison growth has no parallel in western societies. The extraordinary prison expansion involving young black men is grossly disproportionate; achieving another historic record: most of the people sentenced to time in prison today are black. On any given day, nearly one-third of black men in their twenties are under the supervision of the criminal justice system-either behind bars, on probation, or on parole. Blacks are about eight times more likely to spend time behind bars than whites.

Although deprivation of family contact may be seen as part of an individual offender’s deserved punishment, the damaging consequences to families, social networks, and communities must be added to the social costs of mass incarceration. The negative impact of a short-term exposure to prison suggests that growing up in neighborhoods where prisons have saturated everyday life inflicts tremendous damage on children creating what James Finckenauer calls a “delinquency fulfilling prophecy”.1

Researchers find that incarceration has become a systemic aspect of community members’ family affairs, economic prospects, political engagement, social norms, and childhood expectations for the future.2 Rather than pointing the finger at discrimination by prejudiced individuals, researchers reveal how whites benefit from “structural favoritism” built into U.S. policies, institutions, and cultural representations, that endures for generations.3 Seven percent of black children had a parent in prison in 1999, making them nearly 9 times more likely to have an incarcerated parent than white children.4 Separation from imprisoned parents has serious psychological consequences for children, including depression, anxiety, feelings of rejection, shame, anger, and guilt, and problems in school.5 Incarceration is a “rite of passage” imposed upon African American teenagers.6 Some respond to their enforced identity as poor fathers by distancing themselves from their children, minimizing the father role in their sense of themselves.7

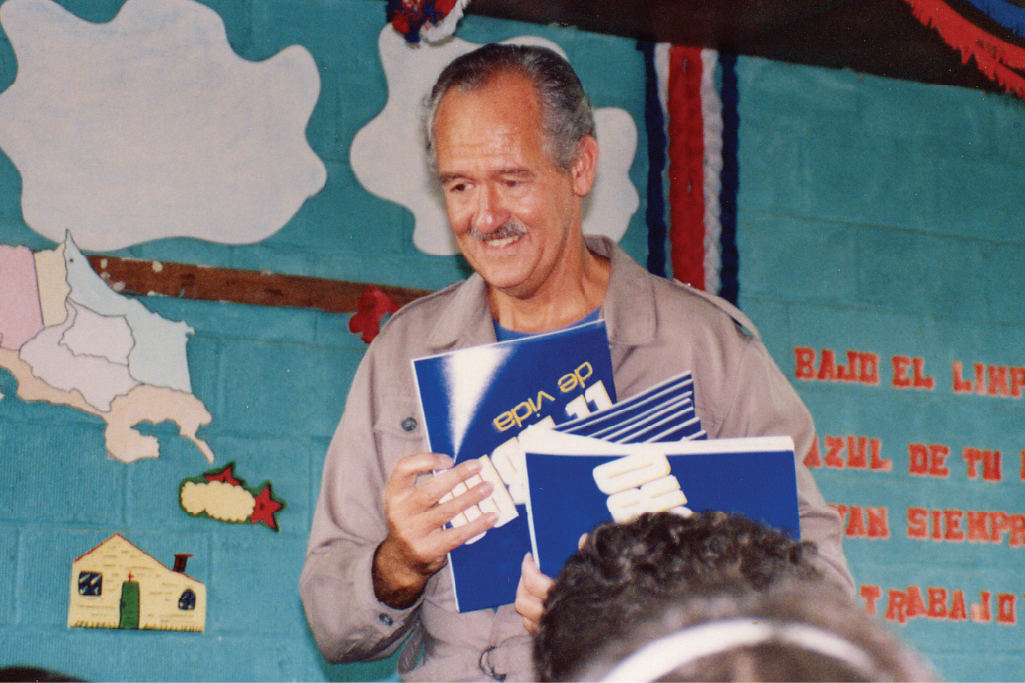

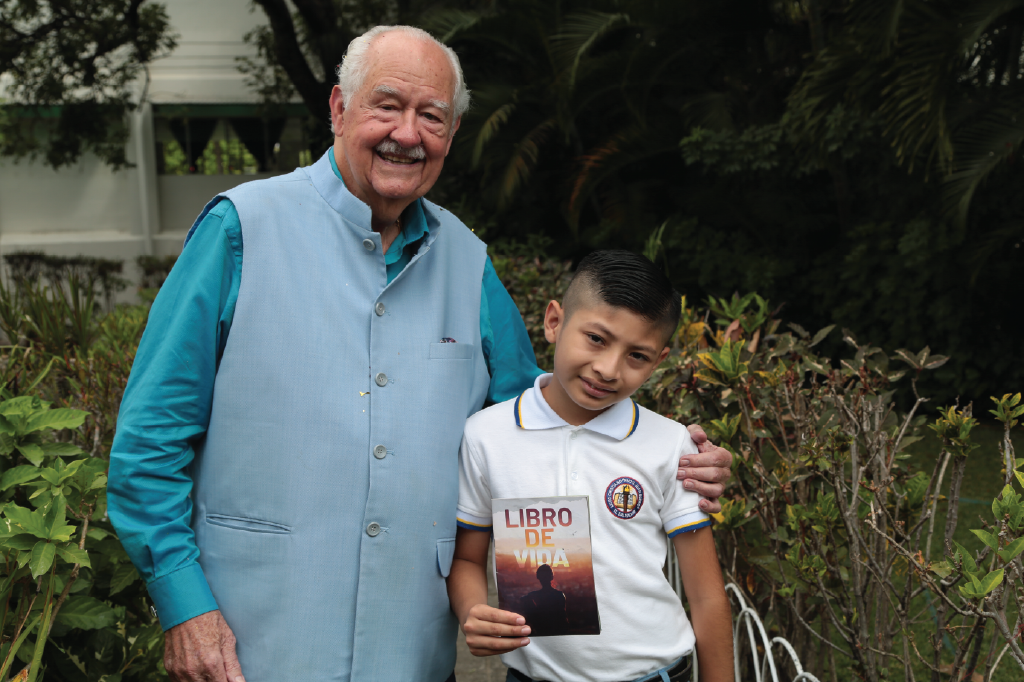

OneHope in partnership with Angel Tree, a Prison Fellowship ministry designed a special program to try and help to meet the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of children of incarcerated parents. To share Christ’s love with them and also attempt to break the cycle of the “delinquency fulfilling prophecy.”

Angel Tree serves as a connection between prisoners and their families by sending gifts on the families’ behalf … delivering a message of love from the parent to the child.

In every gift package, OneHope provides a specialized Book of Hope, speaking to the heart-felt needs and issues children of inmates face, such as fear, abandonment, and loneliness. We also present a Book of Hope to the caregivers and the imprisoned parents of these children. Last year, the program reached 298,000 and so far this year we’ve 2015 reached well over is 301,000!

In many ways the Evangelical community has forgotten the command to ‘remember those who are in prison, as though in prison with them’ from Hebrews 13:3. The growing prison population, particularly the disproportionate Black population, is part of our mission. Continually voting for stricter prison sentences should not be our primary response to an ever deepening problem, reaching out in love to these children who are victims should be a priority mission of the US Church.

Sources:

1. THE SOCIAL AND MORAL COST OF MASS INCARCERATION IN AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITIES Dorothy E. Roberts , Stanford law review.

2. William J. Chambliss, Drug War Politics: Racism, Corruption, andAlienation, in CRIME CONTROL AND SOCIAL JUSTICE, supra note 1, at 295, 297-99; JEFFREY FAGAN, VALERIE WEST & JAN HOLLAND, RECIPROCAL EFFECTS OF CRIME AND INCARCERATION IN NEW YORK CITY NEIGHBORHOODS 5 (Columbia Law Sch.l Pub. Law & Legal Theory Working Paper Group, Working Paper No. 03-54, 2003) available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=392 120 (last visited Mar. 5, 2004).

3 Lehrman, Colorblind Racism, supra note 4 8 (paraphrasing Andrew Barlow).

4 CHRISTOPHER J. MUMOLA, U.S. OEP’T OF JUSTICE, INCARCERATED PARENTS AND THEIR CHlLDREN (2000), available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/iptc.pdf ( last visited Mar. 28, 2003).

5 Sandra Lee Browning, R. Robin Miller & Lisa M. Spmance, Criminal Incarceration Dividing the Ties That Bind: Black Men and Their Families, in IMPACTS OF INCARCERATION ON THE AFRICAN AMERICAN FAMILY,

6 Jerome Miller, Bringing the Individual Back In: A Commentary on Wacquanl and Anderson, in MASS iMPRISONMENT.

7 Brad Tripp, Incarcerated African American Fathers: Exploring Changes in Family Relationships and the Father Identity, in IMPACTS OF INCARCERATION ON THE AFRICAN AMERICAN fAMILY, supro note 60, at 1 7, 27.